The Rule of 40 - A Better Alternative to Value Growth Stocks

Traditional valuation metrics such as P/E or P/B are useless for evaluating technology and growth stocks. An alternative indicator can help.

This is the third part of a blog series in which I describe the basics of my stock-picking strategy. I strongly recommend that you read High-Growth Investing 101, Part 1 and Part 2 before reading this article.

Anyone who takes the stock market seriously learns about classic valuation metrics such as the price/earnings ratio (P/E ratio) and the price/book ratio (P/B ratio) as part of their basic training. For decades, these have been considered the basics of fundamental stock valuation. However, in the age of digitalization and AI, this basic knowledge is often useless for stock analysis.

With this in mind, I would like to present an alternative metric that is just as easy to calculate, but much more suitable for filtering out potential outperformers from an investment universe of technology and growth stocks.

The problem of P/E

Recent years have seen the creation of disruptive companies at an unprecedented speed, particularly outside the stock market. Worldwide, there are now more than 1,200 so-called unicorns, i.e. pre-IPO start-ups financed by venture capital with a valuation of more than 1 billion USD. As many as 53 of them belong to the so-called decacorns, which are unicorns with a valuation of at least 10 billion USD.

Many of these companies will make their way to Wall Street in the coming years. Given the size they have already achieved, many of these high-growth companies are likely to claim a place on the S&P 500 index of the 500 most valuable US listed companies very soon after their IPO. The prediction by strategy consultants Innosight that more than half of the companies in the S&P 500 will disappear in the next ten years, replaced by faster-growing competitors, therefore seems realistic.

These new and disruptive companies are focused on maximizing growth and becoming cash flow positive. Short-term GAAP profitability is not yet the focus of management. As long as the cost of customer acquisition is favorable in relation to the revenue that can be generated over the life of the customer relationship, this makes sense from a shareholder value perspective. If you want to assess the performance of such companies, the P/E ratio based on GAAP earning is not very helpful.

Such "revenue first" strategies are nothing new: many of today's digital world leaders have created enormous value for their shareholders before ever turning a profit. Amazon, for example, lost money for seven years after its IPO in 1997. Even in the twelve years that followed until 2016, Jeff Bezos was not interested in profits, only in growing into new businesses. This meant that Amazon's P/E ratio was useless for its first 20 years as a listed company. During that time, however, the share price multiplied from 1.50 USD to over 1,000 USD.

Since its IPO in June 2004, cloud software leader Salesforce has not made a significant profit until 2018, deliberately investing all of its cash in growing its addressable market. In the 15 years since its IPO, the company's value has increased 70-fold, from 4 USD to 280 USD.

Investors who use the P/E ratio as a key valuation metric have not been part of these success stories and will stay at the sidelines as the best of today's unicorns become tomorrow's global market leaders.

The P/B is not an option

Unfortunately, traditional asset-based metrics such as price-to-book (P/B) ratios are no longer useful for valuing high-growth companies. This is because the most important assets of such companies tend to be intellectual property and network effects. However, these assets are usually not on the balance sheet if they have been created organically rather than as part of an acquisition. As a result, they are typically excluded from traditional book value calculations.

However, intrinsic value becomes apparent when another SaaS or platform company is acquired by a strategic buyer at a breathtaking price. Many investors then rub their eyes in amazement as the prices paid cannot be reconciled with the key figures of traditional fundamental analysis.

In conclusion, P/E, P/B and many similar indicators of traditional fundamental analysis are useless for valuing growth stocks. A different approach is needed to value growth stocks.

The efficiency score of the "Rule of 40" as an alternative

The "Rule of 40" can be used to assess the efficiency of a company's growth and therefore the quality of its business model - even for companies that are not yet profitable. The "Rule of 40" describes the simple principle that a company's combined growth rate and profitability margin should exceed 40 percent. It has become an important benchmark in recent years, particularly in the venture capital and growth equity sectors.

Software executives are increasingly using the "Rule of 40" as a key management metric to successfully navigate their organizations through the constant trade-off between investing in growth - including new products and customer acquisition - and short-term profitability.

US venture capitalists began popularizing the Rule of 40 about 10 years ago as a quick benchmark for pre-IPO SaaS (Software as a Service) companies. But it is also very applicable to the vast majority of public software and digital platform companies across a range of industries.

The Rule of 40 score, also known as the efficiency score, is defined as the sum of sales growth and free cash flow margin. It is expressed as a percentage. The higher the score, the better the business model.

Efficiency Score (%) = Sales Growth TTM (%) + FCF Margin TTM (%)

Analysts disagree on which measure of profitability should be used for the calculation. The use of EBITDA is often suggested. However, I prefer free cash flow (FCF), defined as operating cash flow plus cash flow from investing activities.

The FCF cannot be manipulated by accounting tricks and shows how much money is actually left over for a company's shareholders. I prefer to use figures from the past 12 months (TTM = trailing twelve months) for the calculation in order to eliminate the seasonal effects.

The "Rule of 40" in practice

The "Rule of 40" states that a negative cash flow rate (= burn rate) of 20 percent is still perfectly acceptable for a young company that is growing explosively at 60 percent per year.

However, once the percentage growth slows down as the company grows and falls to 40 percent per year, free cash flow should break even. This means that the company should no longer need external funds to finance its growth.

And if growth slows to, say, 10 percent later in the company's development, the free cash flow margin should exceed 30 percent.

The efficiency score over time

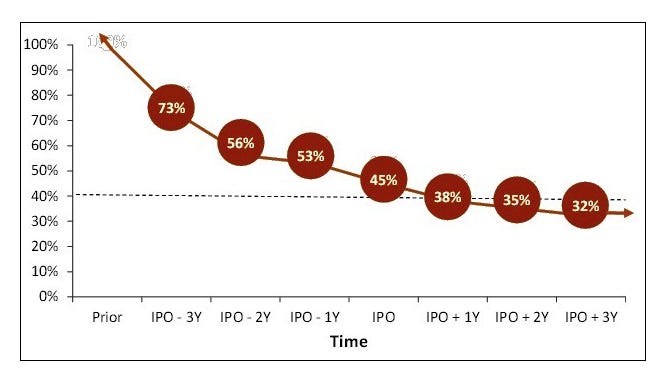

The efficiency score therefore provides a good indication of how successful a business model really is at any point in the company's life cycle. This key figure tends to fall as the company grows in size in the years following the IPO. US venture capital firm Bessemer has calculated that the average efficiency score for listed SaaS companies falls by as much as 10 percentage points in the two years following the IPO.

It is therefore important not only to determine the efficiency score once, but also to track its development over time. Only the very best companies are able to keep their score constant over many years. Management consultants Bain+Company found that while 40 percent of all larger software companies met the "Rule of 40" in a single year after going public, only 16 percent managed to do so over a five-year period.

Correlation between efficiency score and share price

It is therefore not surprising that a company with a high efficiency score tends to trade at an above-average sales multiple on the stock exchange. Indeed, Bessemer found an astonishingly high correlation of over 70 percent, which can be read in this interesting article about the "Rule of 40".

There is also a clear trend line in my sample portfolio.

Deviations above the trend line (e.g. CrowdStrike CRWD 0.00%↑ , Veeva Systems VEEV 0.00%↑ ) indicate that the stock may be overpriced, while stocks below the trend line (e.g. ZoomInfo ZI 0.00%↑ , Airbnb ABNB 0.00%↑ ) tend to be discounted.

It can be assumed that the shares of companies with a high efficiency score will be valued on the stock market at an above-average EV/sales ratio. However, it is not only stock market players who are interested in the "Rule of 40" as a benchmark. It can be observed that companies with a high Efficiency Score are particularly often acquired at a strategic price.

Conclusion

The " Rule of 40 " is ultimately a fairly reliable method of assessing the efficiency of growth, even for a company that is still unprofitable. Best of all, this valuable indicator is incredibly easy to calculate and interpret.

Of course, the "Rule of 40" is only a rule of thumb and cannot replace a well-founded fundamental analysis. However, it can be a very useful tool, for example when using a stock screener such as Stocksguide.com to find interesting growth stocks.

On this Substack I will published many articles around my stock picking strategy as well as concrete investment ideas.

If you are interested in the High Growth Investing strategy, don’t miss to read the following articles from this series:

When is the right time to exit a stock?

This is the second part of a blog series in which I describe the basics of my stock-picking strategy. I strongly recommend that you read High-Growth Investing 101, Part 1 before reading this article.